An interview with Richard Kigel, author of Heav’nly Tidings From the Afric Muse: The Grace and Genius of Phillis Wheatley

Richard Kigel is a historian and educator with an interest in 18th and 19th-century American history. His first book, Becoming Abraham Lincoln: The Coming of Age of Our Greatest President, recounts Lincoln’s early life using firsthand accounts.

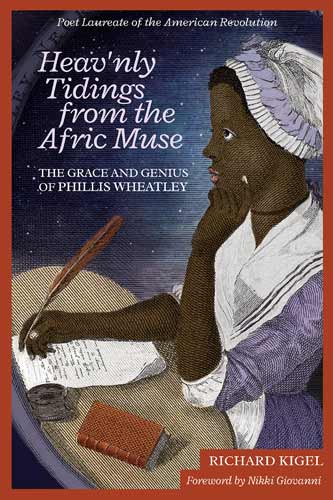

Kigel’s second book, the exhaustively researched biography of African American poet Phillis Wheatley, Heav’nly Tidings from the Afric Muse: The Grace and Genius of Phillis Wheatley, was published in 2017 by Paragon House. It includes a foreword by Nikki Giovanni, who says, “I think this book should be read by every poet to remind us how precious our freedom really is.”

The book has received widespread praise. Henry Louis Gates has said, “With this masterful biography, she will be restored to her rightful place as a major figure in the intellectual history of the fledgling American Republic. Every student and scholar of American literature should read this well-written and carefully researched biography.”

Yusef Komunyakaa says, “Heav’nly Heav’nly Tidings From the Afric Muse: The Grace and Genius of Phillis Wheatley, is not only timely but also written out of a robust respect for this poet whose eloquence subverted the stereotype of the African. This book captures a young woman in bondage who possessed the courage and audacity to rise within that peculiar institution to speak as a seer, as an early American poet who dared to praise the imagination as the capstone of human experience. Kigel gives us a servant of language, a truth-teller who survived with an amazing grace, and whose dynamic work continues to challenge us across centuries.”

I interviewed Richard Kigel about the book, some surprises encountered during his research, Phillis’ life, and what she has to teach us today.

DE: How was your interest in Phillis Whitney first sparked, and why did you write this book?

RK: Growing up in the 1960s, I was right in the middle of the civil rights protests, marches against the war, acrimonious debates and devastating assassinations. I remember watching a TV special called Black History: Lost, Stolen or Strayed. It was probably the first program ever to focus on Black History and it really opened my eyes. That was the first time I realized that a huge area of American history was basically hidden. I was intrigued enough to look into it so I went out and bought the book.

By the 1970s I was teaching in a predominantly black neighborhood in Brooklyn when the groundbreaking TV series Roots captivated the nation. That was a huge cultural moment. Teachers saw how we could use the power of those stories to inspire our students. It became clear that we can’t even begin to understand the American character unless we include these heroic stories of African Americans. Black History became a thing and I came to the conclusion it is all part of American history.

So all my adult life I was attuned to Black history. About ten years ago I was having a conversation with someone about the amazing achievements of African-Americans when Phillis Wheatley’s name came up. I didn’t really know very much about her other than her name and some basic facts about her life—she was a slave who wrote poetry. I became curious about her life and her work. What was she actually like? How did she come to write poetry? Was her work any good?

I read some of her poems and was impressed by her deep spirituality and the clarity and sophistication of her imagery. I went looking for a biography of Phillis Wheatley and was surprised to find there were none. There were plenty of books on Phillis Wheatley but they were all written for children and young adults. So I decided to write one.

I kind of fell in love with Phillis Wheatley and her poetry and knew that her story needed to be told. Right now she is so disconnected from our cultural awareness that hardly anybody knows anything about her beyond the bare outlines of her life. Who can cite even the title of one of her poems?

When I tell people about my new biography of Phillis Wheatley I get this quizzical look, the raised eyebrow, then, maybe, “‘who?”

And that is why we need this biography of Phillis Wheatley.

DE: While doing research about Phillis, what did you learn that most surprised you?

RK: There were two moments during my research when I discovered something so startling I almost fell out of my chair. Phillis had a line in a letter to one of her friends where she talks about the imminent arrival of her books. “I expect my books which are published in London in Capt. Hall, who will be here I believe in 8 or 10 days,” she wrote on October 18, 1773.

Suddenly it hit me. I knew from my research that James Hall was the captain of The Dartmouth, the first ship carrying East India Tea that arrived in Boston on November 28, 1773. It meant that Phillis’s books were on that ship. We have it in her own words.

Logs from The Dartmouth revealed that all the cargo was unloaded except for the tea so Phillis was able to claim her books. Three weeks later a band of colonists disguised as Mohawks sneaked on board the three tea ships and tossed all the tea into the harbor in what we know as the Boston Tea Party.

I am proud of the fact that I was able to confirm this as historical fact, not by discovering any new information, but by connecting the dots representing what we already knew. This gives a huge boost to the legacy of Phillis Wheatley. There is a powerful irony in the fact that her own creative offspring, her poems, made the same trans-Atlantic journey as she did as a captive. Now Phillis Wheatley is forever linked to one of the most iconic moments in American history.

Another eye-popping moment occurred while I was looking into the report about the meeting between Phillis and George Washington. The only description of this meeting was written seventy-four years later by a journalist named Benson Lossing. Because of the time lag and lack of primary source support, historians have been skeptical. Some call it a myth. I wanted to look deeper to see if I could find any new details that would shed light on the question: did Phillis Wheatley actually meet George Washington?

Lossing’s original assertion about Phillis and Washington appeared in the November 1850 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. I hunted it down and the moment I found the issue in an internet archive, what a thrill! It was like finding gold.

I was able to read his statements on the Wheatley-Washington meeting in context. Earlier in his piece, Lossing described the circumstances of his visit to the house in Cambridge that Washington used as his headquarters. He mentions that he spoke to the owner of the house whom he identifies as the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. So I wondered—was Longfellow the source for Lossing’s information on the Wheatley-Washington meeting?

I played detective, hunting up documents, journals, and diaries. I found an entry in one of Longfellow’s journals for Friday, October 6, 1848 where he mentions a visit by Mr. Lossing who was working on an article for Harper’s. This confirmed that Benson Lossing actually did interview Longfellow at the very house Washington used as his headquarters, the same house where he presumably met Phillis.

Later I discovered that one of the residents of that house along with Longfellow was Jared Sparks, a Harvard professor who, at the time, was working on the monumental task of editing all George Washington’s letters. Sparks declared: “The entire mass of Washington’s papers, amounting to forty thousand letters, is now in the room where I am writing.” Among the forty thousand letters in Sparks possession at the Longfellow house was the extraordinary letter Washington wrote to Phillis on February 28, 1776 where he invited the poet to visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge.

Now I had a new question: was Longfellow aware of this letter and the fact that Washington, himself, had invited Phillis to visit him at the house?

More digging turned up another intriguing clue. Longfellow told his father that he was reading Washington’s letters from Sparks’ collection. This puts the original letters of George Washington into Longfellow’s hands, including his letter to Phillis. It seems unthinkable that Sparks would fail to show his poet friend the letter addressed to the famous black slave poet since Washington invited her to that very house.

Even if Longfellow actually read Washington’s letter inviting Phillis to visit him, we have to ask how he learned that the visit actually took place. Longfellow did not live in the house until sixty years after the supposed Wheatley-Washington meeting. How would he know about such a meeting? Who could have been his source?

Another researcher did some monumental work uncovering the history of the Cambridge house Washington used as his headquarters. Previously it belonged to a wealthy Tory family but when hostilities between British forces and the colonists heated up, the family fled to London. Among the property they abandoned were several families of slaves. They were still legally enslaved but since their masters were gone they were essentially free. The slaves remained in their homes on the property for generations living in defacto freedom.

One of those slaves was named Darby Vassall. He was a young boy when Washington came to the house but often told the story of meeting the General on the property. I found an entry in Longfellow’s diary where he wrote about a pleasant visit by “Old Mr. Vassall, born a slave in this house in 1769.” They knew each other well. Darby Vassall could tell him stories about Washington’s stay there. It is easy to see how he could have told Longfellow about Phillis Wheatley’s visit.

And there were other possibilities. One of Longfellow’s great friends for over fifty years was George Washington Greene. G. W. Greene was the grandson of Nathanael Greene, one of Washington’s most trusted generals who was a constant presence at Washington’s side and was with him at his Cambridge headquarters. When Lossing wrote: “She passed half an hour with the Commander-in-chief, from whom and his officers she received marked attention,” it is highly likely that he was referring to General Greene. That would make him an eyewitness to the Wheatley-Washington meeting. It is not a stretch to suppose that the story of the Wheatley visit was repeated in the Greene family and known to Longfellow’s friend. Perhaps G. W. Greene was Longfellow’s source.

The most telling piece of evidence supporting Lossing’s report of the meeting came from Longfellow himself. Following their interview, Longfellow corresponded with Lossing several times, offering minor corrections to his article about the house and giving him an enthusiastic blurb for his book. If Longfellow had a problem with Lossing’s statements on the Wheatley visit or believed it to be unfounded or untrue, he said nothing. By allowing Lossing’s description of the Wheatley-Washington meeting to stand Longfellow gave his tacit approval. The practical effect of his silence was to confirm the story.

Of course, there is no definitive evidence to support the assertion that Phillis came to Cambridge and met Washington there. We have no eyewitness statements, no letters, no mentions in contemporary journals or diaries. But I am proud that I was able to accumulate a substantial body of circumstantial evidence that strongly suggests that Phillis Wheatley did meet George Washington. I do believe that Phillis Wheatley accepted Washington’s invitation and came to visit the general at his headquarters in Cambridge, the report of that meeting originating with someone who was actually there to witness it. The story then was passed down through several generations and shared with the owner of the house, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who related it to the journalist Benson Lossing who included it in his article on the house.

This may not be absolutely ironclad but I think there is enough credible information to allow us to put the question to rest. As Washington’s biographer Ron Chernow wrote: “Washington appears to have received Phillis Wheatley at his Cambridge headquarters.” And that is about as definitive as we can get.

DE: Phillis was brought to this country in 1761 and later corresponded with some of the founding fathers. What did they discuss?

RK: I think it is enormously significant that Phillis Wheatley personally knew and corresponded with five of our Founding Fathers. John Hancock, first president of the Continental Congress and first to sign the Declaration of Independence, was a business associate of Phillis’s owner John Wheatley. He would have been a frequent visitor to the Wheatley home. He was very likely already familiar with Phillis and her poetry when he signed the attestation appearing in her book to confirm that she actually wrote the poems herself.

George Washington wrote a letter of appreciation to Phillis in response to her poem in his honor. He was so impressed that he arranged to have it published and he invited her to visit him at his headquarters in Cambridge.

Phillis met Benjamin Franklin while she was in London. Franklin later wrote about meeting her at the apartment where she was staying and offered his services.

Benjamin Rush, also a signer of the Declaration of Independence, wrote a laudatory review of her work. His wife, Julia Stockton Rush, had copies of her poems. We know that Phillis corresponded with Dr. Rush because she mentions a letter she wrote.

Captain John Paul Jones, hero of the Continental Navy (famous for declaring: “I have not yet begun to fight!”) sent some of his own poetry to Phillis along with a note. “Pray be so good as put the enclosed into the hands of the celebrated Phillis the African favorite of the Nine and of Apollo.”

The fact that Phillis Wheatley had a personal relationship with so many of our Founding Fathers tells us how highly regarded she was in her time. This was a closed circle, the elite of society, the privileged class. They were the leaders of the country and interacted almost exclusively with each other. There would have been little reason to have contact with ordinary folks, especially women who were second class citizens at the time and with black people who were invisible as non-persons.

So having substantial contact with five of the nation’s leaders is a big deal for anyone. It shows that Phillis Wheatley had a sort of select membership in an exclusive club. For an African American woman, this is absolutely amazing. And it is only one of several arguments we can make to support the claim that Phillis Wheatley belongs in any conversation about our Founding Fathers and Mothers.

DE: Phillis often wrote poems which addressed the political and societal concerns of the day. How was she regarded as a poet during her lifetime? Did she have an impact on the political thought of the time?

RK: During her lifetime Phillis Wheatley established herself as a widely respected poet on two continents. When Phillis sailed to London in 1773 her trip became something of a media event in in colonial America and Britain. Her departure was covered by newspapers throughout New England—in Boston, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, and New York. She was described as “the extraordinary Negro poetess,” “the ingenious Negro poet,” or “the extraordinary poetic genius.” In London she was treated as a visiting celebrity. Henry Louis Gates says that Phillis Wheatley was “the Oprah Winfrey of her time.”

Her books were on sale throughout the colonies and even in Canada. Copies have been found in South Carolina. Thomas Jefferson owned a copy of her book.

What kind of impact did she have on her contemporaries? That is a complicated question. At that time and roughly for the next two hundred years, African Americans were denied any but the most demeaning participation in our national life. Phillis Wheatley was a player. Her eloquence and artistry were inserted into the cultural bloodstream of the nation.

A black woman writing poetry? It was unheard of. Her very existence was a direct challenge to the dominant belief in white European supremacy. Suddenly white people had to consider new ways of thinking about these Africans in America—and for many, this radical idea brought resistance and denial. Here was a thoughtful, dignified, highly educated black woman contributing to American literature. By her intelligence and creative power in the face of virulent white supremacy, Phillis Wheatley forced the culture around her to acknowledge her humanity.

George Washington was clearly impressed by Phillis Wheatley. He received her poem at a time of heightened gloom for the new Continental Army. He had just been installed and was appalled at the manpower shortage he found. Just weeks before he read her poem General Washington took the unprecedented step of allowing the recruitment of “free negroes” to fight in the Continental Army, making it the most integrated American fighting force before the Vietnam War.

The Commander-in-Chief was moved to take a startling, almost unthinkable step for a Virginia aristocrat and slave-owner. He sat down to write what was the most extraordinary letter of his career. General Washington composed a personal message to Phillis Wheatley, thanking her for her letter and particularly the poem and inviting her to come for a social call. According to Washington biographer Joseph Ellis, it was “the only occasion in his correspondence when he directly addressed a slave.”

The meeting with Phillis and his admiration for the performance of black soldiers became part of a gradual shift in Washington’s thinking about the institution of slavery.

Although he continued to own slaves until the end of his life, his will stipulated that all his slaves should be freed. Among the Founding Fathers he was the only one to grant his slaves their freedom.

DE: What was the most difficult part of the research?

RK: I would have to say the note-taking and organizing. What I found amazing was how readily available so many primary source documents are on the internet. I could read newspapers from the 1770s, books published two hundred years ago and even other scholars’ more recent work. Sometimes it invited information overload.

DE: Phillis was unusual among slaves in that she was taught to read and write. How did that come about?

RK: Not long after Phillis arrived in Boston as a child, the Wheatley family began noticing something startling about their new slave girl. A member of the Wheatley family wrote that “She soon gave indications of uncommon intelligence and was frequently seen endeavoring to make letters upon the wall with a piece of chalk or charcoal.”

Another Wheatley family member wrote that “By seeing others use the pen, she learned to write.”

Her master John Wheatley said: “As to her writing, her own curiosity led her to it.”

John Wheatley offered his own testimony to confirm his slave’s exceptional abilities.

“Phillis was brought from Africa to America in the year 1761, between seven and eight years of age. Without any assistance from school education, and by only what she was taught in the family, she, in sixteen months time from her arrival, attained the English language to which she was an utter stranger before, to such a degree, as to read any most difficult parts of the sacred writings to the great astonishment of all who heard her.”

To their great credit, the Wheatleys established an atmosphere in their home that would support and encourage their gifted young slave as she progressed in reading and writing. Phillis was a precocious child and the Wheatleys offered her an extraordinary opportunity to develop her talents and interests.

“She never was looked on as a slave,” one of her Boston neighbors said.

Few Bostonians had the luxury of light in their bedrooms and only the most fortunate had the comfort of warmth during those brutal New England winters. Phillis had both.

Despite her legal status as property of the Wheatleys, she had considerable freedom to pursue her own inspirations in her writing. “She was allowed, and even encouraged, to follow the leading of her own genius,” a Wheatley family member said. “But nothing was forced upon her, nothing suggested, or placed before her as a lure; her literary efforts were altogether the natural workings of her own mind.”

DE: Do we know which other poets’ and writers’ work Phillis read, or what her poetic influences were?

RK: Phillis met some of the most learned men of Boston who visited her at the Wheatley home. Many of them gave her books and helped her study the great literary works of her time. Her poetry shows that Phillis was well versed in the scriptures of the Old and New Testament, Greek mythology as well as Shakespeare, Horace, Virgil, Ovid, Terrence, Milton and her favorite, Alexander Pope.

DE: Did other slaves know of her and her work?

RK: The first person of African descent to publicly acknowledge the poetry of Phillis Wheatley was Jupiter Hammon, a Long Island slave. It was Jupiter Hammon who became the first black poet published in America. His poem, “An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ with Penitential Cries“, appeared in 1760, a year before the Middle Passage brought Phillis Wheatley to Boston.

In August 1778, Jupiter Hammon’s poem “An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatly, Ethiopian Poetess, in Boston, who came from Africa at eight years of age, and soon became acquainted with the gospel of Jesus Christ” was published in Connecticut.

Jupiter Hammon addressed Phillis Wheatley directly.

Come you, Phillis, now aspire,

And seek the living God,

So step by step thou mayst go higher,

Till perfect in the word.

Come, dear Phillis, be advis’d,

To drink Samaria’s flood;

There nothing is that shall suffice,

But Christ’s redeeming blood.

When thousands muse with earthly toys,

And range about the street,

Dear Phillis, seek for heaven’s joys,

Where we do hope to meet.

In 1782 the first deeply personal response to Phillis Wheatley written by a native African and former slave was published. Ignatius Sancho, born a slave in London and eventually freed, wrote the most poignant and passionate response to Phillis Wheatley’s poetry ever recorded by one of her contemporaries. “The perusal affected me more than I can express,” he wrote. “Indeed, I felt a double or mixed sensation—for while my heart was torn for the sufferings, which, for aught I know, some of my nearest kin have undergone—my bosom at the same time, glowed with gratitude and praise toward the humane, the Christian, the friendly, and learned author of that most valuable book.”

DE: What do you think Phillis would think about the United States today?

RK: That’s hard to say. If we could extrapolate her character traits onto someone living in today’s world, her essential nature would remain the same. Her contemporaries said she was: “gentle-tempered, extremely affectionate, humble, modest, unassuming,” and “dignified.” She displayed an “amiable disposition, innocence” and “purity of heart.”

A family friend described Phillis this way: “I’ll delineate her in few words: humble, serene, graceful, luminous and ethereal.”

She had a sweet loving nature, a penetrating intellect and was deeply spiritual. All these qualities make for exquisite poetry. I think her love of expressive language and imagery means that her impulse to create vivid poems would be unstoppable. The only question is what would be her preferred style or genre. Phillis fell in love with classical themes and the poetry of Alexander Pope. In today’s world she could well be a romantic poet and allow her personal side to come through. She loved to explore spiritual themes. Some of my favorite lines of hers are profoundly relevant today because they are universal. From “Thoughts On The Works Of Providence”:

Infinite Love wher’er we turn our eyes

Appears: this ev’ry creature’s wants supplies;

This most is heard in Nature’s constant voice,

This makes the morn and thus the eve rejoice;

To him, whose works array’d with mercy shine,

What songs would rise, how constant, how divine!

She was never overly political but because she lived in turbulent times she called out British tyranny and racial injustice. I could see her becoming a songwriter in the mold of Mary J. Blige, Lauryn Hill, Jill Scott , Alicia Keys or Erykah Badu.

I would love to be a fly on the wall at a meeting between Phillis Wheatley and African American poets like Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, Gwendolyn Brooks, Maya Angelou, Elizabeth Alexander, Lucille Clifton, Rita Dove, Claudia Rankine and Nikki Finney. I imagine there would be lots of hugging and smiles, spirited wordplay flying all over the room. Our contemporary poets would have questions for Phillis and she would certainly have questions for them.

It would be a fascinating conversation. Man, I would pay to see that.

DE: What do you think Phillis Whitney’s significance is today? What do you hope that readers will take away from Heav’nly TIdings?

RK: These are the points I hope readers take away from this in-depth look at the life and legacy of Phillis Wheatley:

• She was a Middle Passage survivor.

• She arrived in this country as a slave, unable to read, write or speak a word of English and became the first African American and only the second woman to publish a book in America.

• Her own literary gifts, creativity and intelligence in the face of virulent white supremacy forced the culture around her to acknowledge her humanity.

• She was regarded as a genius in her time and despite persistent efforts to discredit the intellectual abilities of people of African descent, genius remains part of her legacy.

• Through her poetry and letters she was an eloquent advocate for freedom and a supporter of the patriot’s cause.

• Her re-imagined portrait of Lady Columbia as a goddess of liberty gave us the first personification of the American spirit.

• She personally knew at least five of our Founding Fathers, all of whom praised her work.

• Her decision to return to Boston from London where she was free made her the first person of African descent to claim an African-American identity.

• The first shipment of her books arrived from London on the same ship as the hated tea, forever linking Phillis Wheatley to one of the most iconic moments in American history.

• Phillis Wheatley can now be considered among the founder Mothers and Fathers of our nation and the unofficial “Poet Laureate” of the American Revolution.

DE: Thanks, Richard, for these insights into one of America’s groundbreaking poets.